Due to climate change, the International Kootenay Lake Board of Control expects increases in unregulated winter flows in coming years. That could lead to challenges in maintaining water elevations at or below target levels in the lake, located in British Columbia just north of the Washington state border. Studies show an increased potential for warmer, wetter and stormier winters and potential impacts on inflow.

Projections suggest that by 2040 there will be more variability in the amount, timing and speed of snow build up and melt, according to US section board secretary Sara Marxen and climate change scientist Chris Frans, both professional engineers with the US Army Corps of Engineers’ Seattle District.

The Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California projects increases to winter flow and temperature in the basin between December and February. This means flow into the basin would peak earlier than the historical range, putting pressure on the board to prevent exceedances of IJC-ordered end-of-winter maximum water level elevations on the lake.

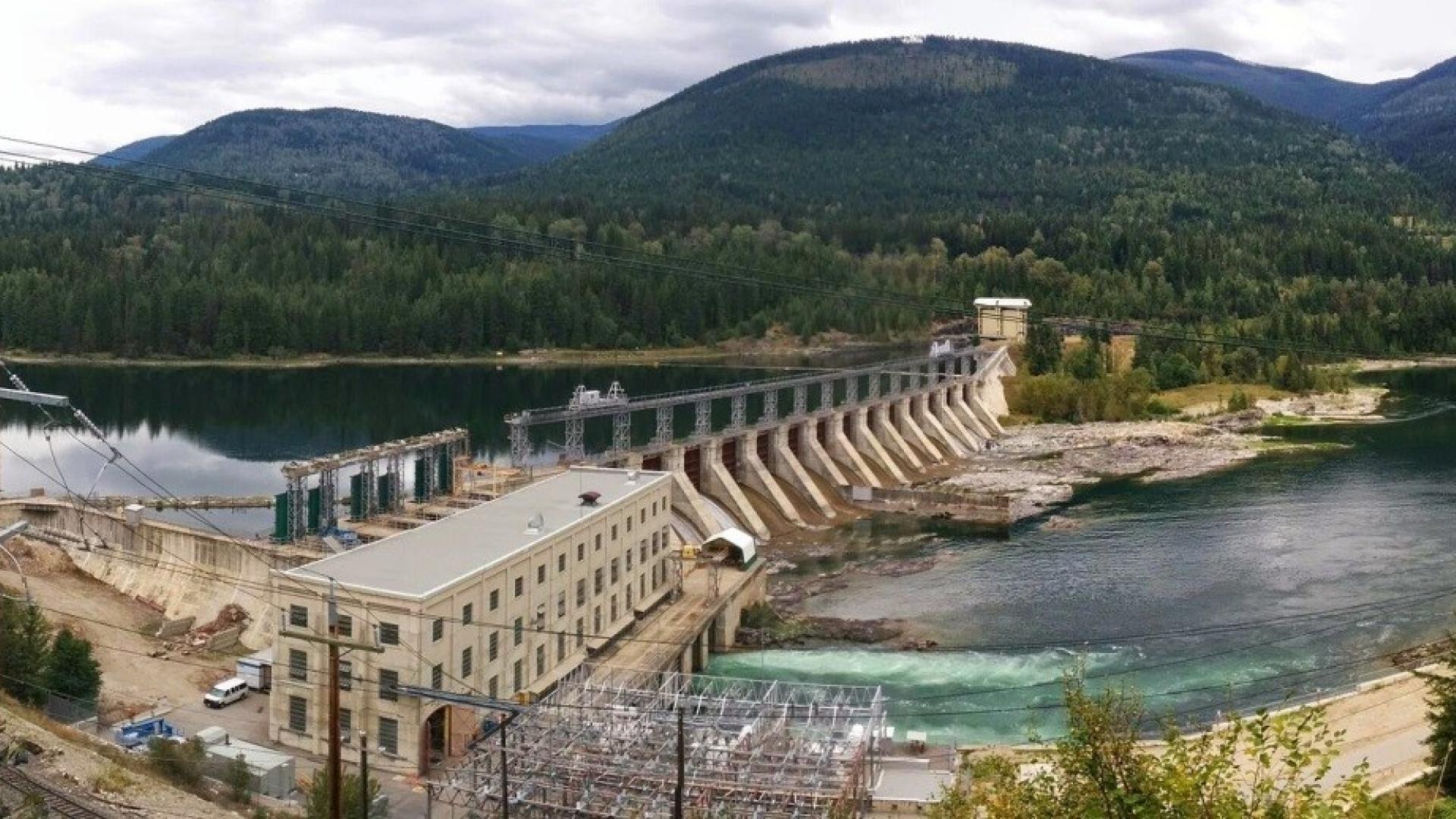

The board is tasked with monitoring FortisBC’s operation of Corra Linn Dam, the primary control mechanism behind the lake’s water level controls. The natural channel constriction in the Kootenay River at Grohman Narrows also restricts the natural outflow of water from Kootenay Lake and plays a role in its water levels.

Under the IJC’s 1938 orders, the board must oversee a drawdown period from January until April and until temperatures lead to the spring rise conditions on Kootenay Lake. The board then oversees a calculated lowering of water levels through the summer and monitors water levels during a storage period through the fall and early winter months.

Board members saw a potential glimpse of the future in 2015, when the river basin received a “decent amount” of snow that melted very early in the year, Marxen said. According to data from Oregon State University’s PRISM program, temperatures were 2-4 degrees Fahrenheit (1-2 C) warmer than the historical average across 2015 on the US side. Information from the Pacific Climate Impacts Consortium found that British Columbia saw record warmth during the winter and spring time period before cooling off in August, with above normal precipitation.

Marxen said projections in the models also suggest the basin could face more precipitation as rain than snow in coming decades. Modeling suggests the basin could see average temperature increases of 5-15 degrees Fahrenheit (3- 8 degrees C) by 2100. That’s compared to the 1980-2010 average, and depends on how global efforts to curb greenhouse gases play out, she said.

A change in precipitation patterns could scramble longstanding regulation plans. While a full analysis of potential impacts hasn’t been completed, increased natural streamflows in the winter months could make it more difficult for the lake level to be lowered below its maximum target elevation by April 1, Marxen said. If the lake exceeds that target, the spring freshet – where upper elevation snowmelt and precipitation bring in a large amount of water – could lead to higher and earlier peak water level conditions on the lake.

The potential for these higher peak water level conditions highlights why adaptive management procedures need to be in place to avoid localized flooding along the river and around the lake, said Canadian Board Secretary Gwyn Graham, transboundary water management manager with Environment and Climate Change Canada. The lake also is affected by regulated inflows from Libby and Duncan dam operations, Marxen said. Depending on how those dam operators adapt to water conditions, Kootenay Lake’s water managers could see different water level outcomes.

In recent months, board members have been talking about the possible implications of these climate change projections. Links and relevant information are available on the board’s website. Other Columbia River basin studies are underway in the United States (updating the River Management Joint Operating Committee, or RMJOC, study) and Canada (updating a BC Hydro study) through 2018 that include hydrological assessments of the basin, Marxen said. The board will be tracking these to glean additional information for future plans.

Kevin Bunch is a writer-communications specialist at the IJC’s US Section office in Washington, D.C.