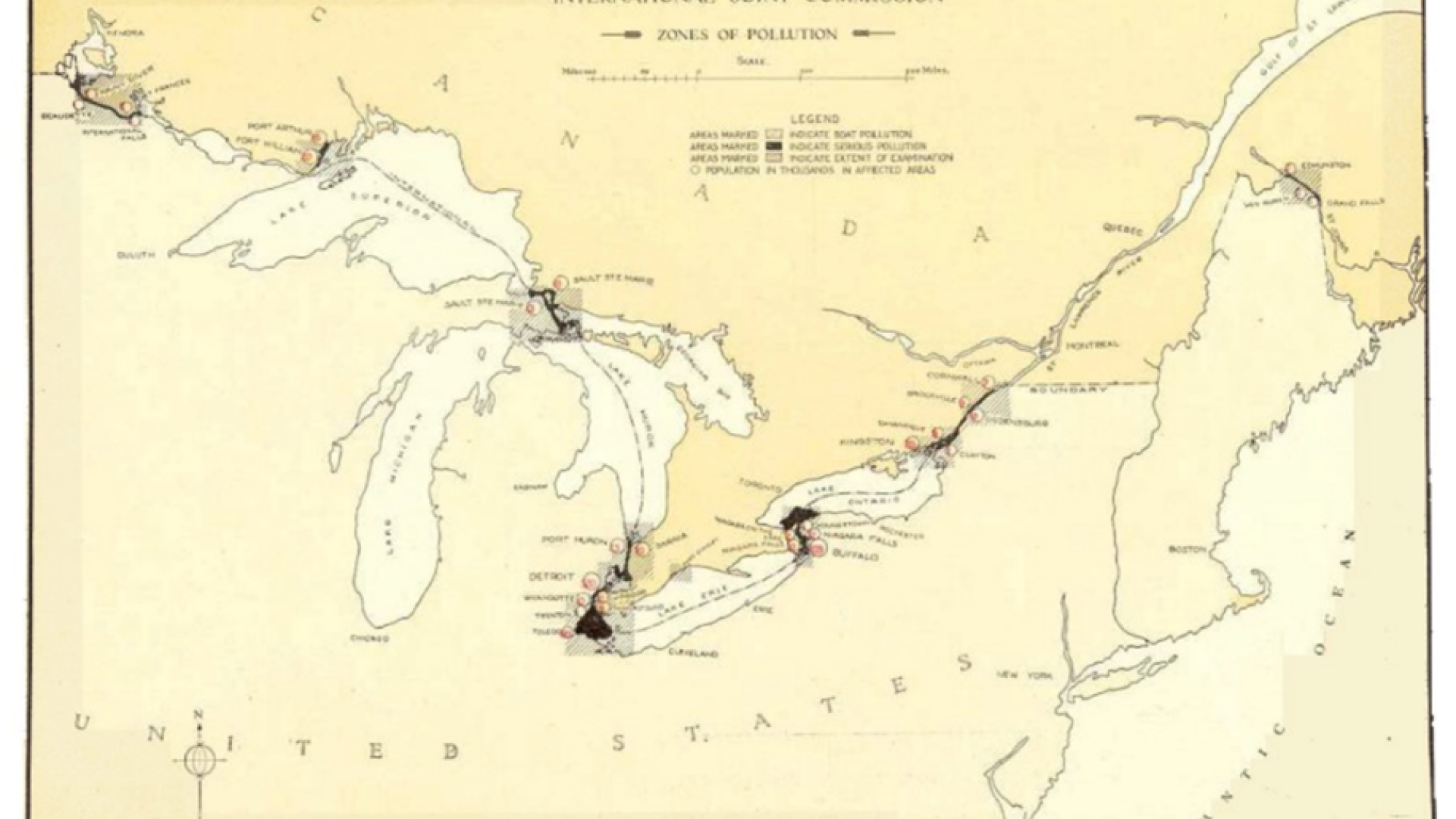

In the early 1900s, concerns about waterborne illnesses and overall water quality prompted the governments of Canada and the United States to direct the International Joint Commission to undertake one of the largest-ever studies monitoring untreated sewage pollution in the boundary waters of the Great Lakes. The study included more than 1,500 sampling locations across four of the five Great Lakes (excluding Lake Michigan) and throughout the Rainy-Lake of the Woods and St. John River basins.

More than 100 years after the original 1913 study, proper fecal pollution management continues to impact water quality and health due to human pathogens found in sewage.

The Great Lakes Water Quality Centennial Study Phase I Report, published by the IJC’s Health Professionals Advisory Board in February 2021, concludes that an updated basinwide water quality survey using cutting-edge DNA technology is feasible and necessary to pinpoint the sources of microbial pollution in the Great Lakes and reduce the risks of illness and disease.

Modern problem, modern monitoring

Thankfully, cholera and typhoid pollution in drinking water sources are problems of the past. However, we are all too aware that the Great Lakes are not entirely free of fecal pollution and the accompanying threats it poses to public health. Today, the lakes are more widely used for drinking water and recreational purposes and both human and livestock populations within the watershed have increased significantly. Additional external pressures, such as climate change-driven weather events and aging sewage and water infrastructure further increase the likelihood that fecal pollution will contaminate the Great Lakes. Advanced contamination source tracking technologies that have become more available are now important tools to solve 21st century water quality problems.

“It is one thing to know that, for example, there is too much bacteria in the waters near a beach to safely swim,” says study co-lead Tom Edge, Health Professionals Advisory Board member and biology professor at McMaster University in Ontario. “But it is another thing entirely to know the source of that bacteria in order to prevent it from contaminating the water again.”

Common sources of bacterial pollution in the region include human fecal waste and animal fecal waste (i.e., agricultural animals, domestic animals and wildlife). However, preliminary results from a survey of beach water quality managers conducted by the board and Great Lakes Beach Association indicate that only one in three managers were certain of the source of fecal pollution at their beaches.

“Using new technology, we can take a water sample, and then track the source of contamination which helps us know how to stop it at its source,” said study co-lead Joan Rose, Health Professionals Advisory Board member and professor and chair in water research at Michigan State University.

“Is it human waste? If so, we may need to fix a sewer overflow or address the numbers of failing septic tanks. Is it waste from cows or sheep? If so, we know we need to examine how to decrease farm runoff. If we deploy microbial source tracking across the basin, then it can point us in the right direction toward preventing the problems.”

Envisioning a basinwide study to track fecal pollution sources

The Phase I report from the Health Professionals Advisory Board offers a framework for how such a large basin source tracking study might be accomplished using new technology to compare bacterial trends and changes. The study framework advises sampling at the original sites as well as additional sites such as Lake Michigan and metro areas including Duluth, Minnesota; Cleveland, Ohio; Hamilton, Ontario; and Toronto, Ontario.

The report advises that a basinwide survey could help to answer key questions:

- Is nearshore water quality getting better or worse?

- Where is the pollution coming from?

- What are the public health risks associated with changing nearshore water quality?

The board’s report further details a suggested framework to guide a future five-year basinwide study using a phased approach—and advises on the objectives that could be achieved during each phase.

The board recommends first convening a committee of federal, tribal, First Nations, Métis, provincial, state and municipal government agencies to design and oversee the study, and the committee would liaise with experts about best practices for applying cutting-edge technologies and assessments. The proposed next phase would involve laboratories throughout the basin that would run tests on the monitoring activities to ensure they will work. The third phase is the action plan: conducting water monitoring and health risk mapping, followed by the final phase analyzing and communicating the findings of the basinwide study.

Next steps

Having established the feasibility and desirability of a basinwide study, the board is now working on its Phase II project to develop an implementation plan for the proposed study. The IJC is not in a position to undertake such a basinwide source tracking study on its own, so for the Phase II project the Health Professionals Advisory Board will engage with experts from the region’s agencies and research institutions to collaboratively formulate an implementation plan.

“Partnerships and collaboration will be key to creating an implementation plan that can feasibly be put into action by the institutions around the table,” says Edge. “But just like in 1913, the IJC’s unique role as leader and convener can help us once again conduct a ground-breaking study that contributes to protecting human health in the Great Lakes basin.”

Alexis Lashbaugh is a former student intern with the IJC’s US Section in Washington, D.C.