The Great Lakes are different today than they were in the past, thanks to invasive species, changes in land use and climate change. Indigenous peoples living in the region for thousands of years are today are working to safeguard lands and species important to their culture and way of life to ensure that they’ll still be here in the decades to come.

Both of the projects featured in this article have come out of work by the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission’s Tribal Adaptation Menu (See also: “Indigenous Knowledge Leading on Climate Change Adaptation in the Great Lakes”).

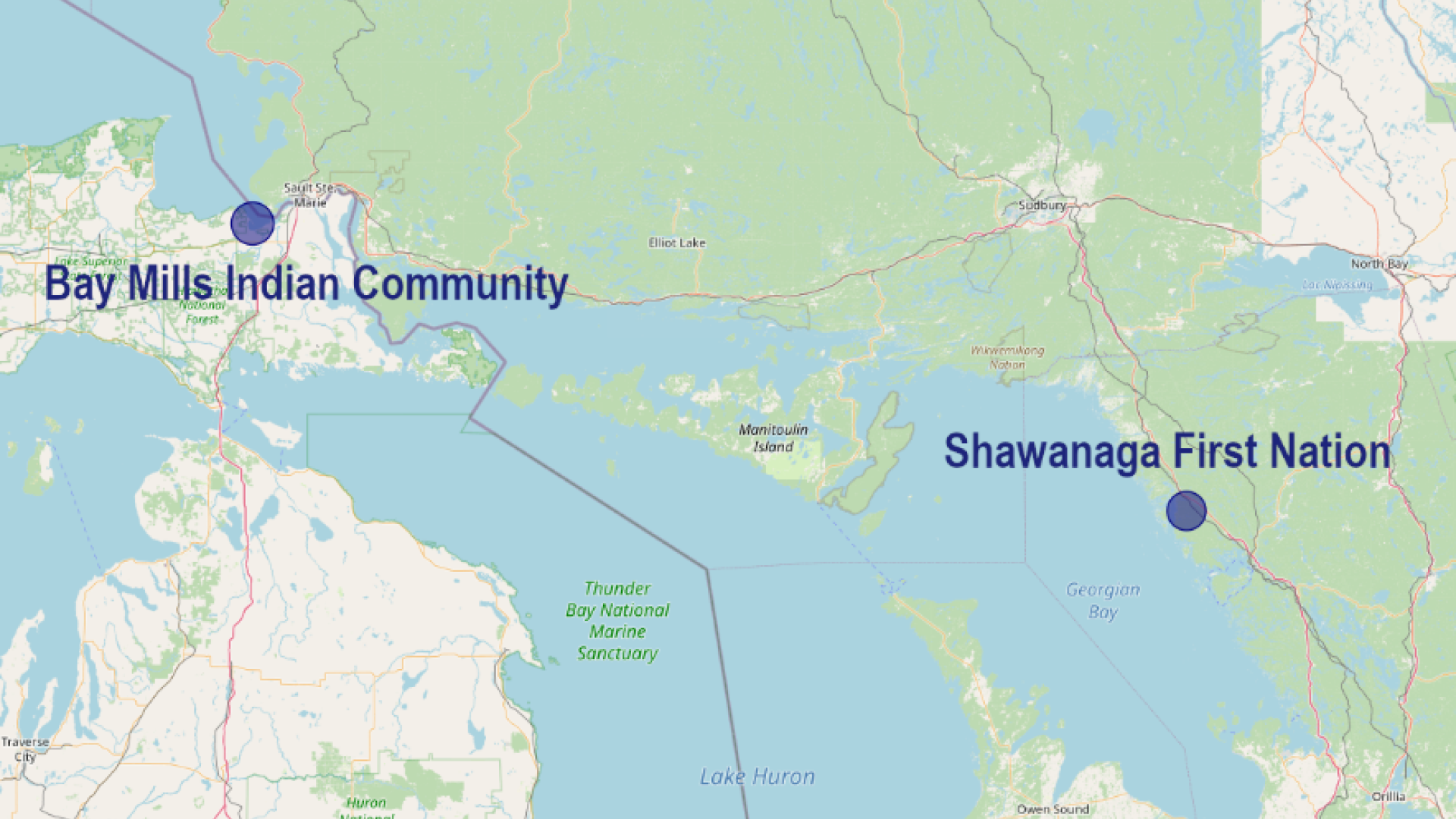

Protecting Shawanaga Island

Situated in Georgian Bay, Shawanaga Island fits within the Georgian Bay Biosphere Reserve and is 1,040 hectares of assumed crown land. In 2019, the Shawanaga First Nation started work to establish the island as an Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area, or IPCA, which would set the island aside – including nearshore waters, inland waters and coastline – for cultural, traditional and conservation purposes.

Shawanaga Island is largely made up of bedrock plains and white pine forests, serving as home to a variety of birds, reptiles, mammals, insects, plants and fish, including the endangered eastern massasauga rattlesnake, according to a Shawanaga fact sheet.

Funding for the effort, up to CDN$1 million over four years, has come through Environment and Climate Change Canada’s Nature Fund, said Chris Burtch, IPCA coordinator for the Shawanaga First Nation. Burtch noted that this is part of Canada’s Target One initiative that aims to protect 17 percent of all of the country’s inland waters by the close of 2020.

“It’s a way for the Shawanaga First Nation to self-govern Shawanaga Island through traditional knowledge and cultural aspects,” Burtch said.

Currently, the First Nation and its partners are working on what Burtch called “foundational work:” environmental studies into the current and historic environmental and usage conditions on the island using a combination of western science and Indigenous ecological and historic knowledge.

Members of the Shawanaga First Nation use the island for ceremonies, hunting and gathering, he added. The First Nation encourages studies that can inform its long-term management plans to ensure that cultural and environmental aspects are safeguarded.

The effort in its early stages, said Alison Gamble, environmental scientist with Shared Value Solutions, a consulting firm in Guelph, Ontario, and a partner organization. Gamble said the island has several ecological and biological areas of interest, as well as historic sites that have played ceremonial and cultural roles over the centuries.

Once the foundational work has been completed, Gamble said they expect to have a proper understanding of the ecological condition of the island and what steps the partners should, and could, take to protect the environment there from degradation. Funding for this research runs through March 2023, and the Shawanaga First Nation and Shared Value Solutions are working with a number of local conservation organizations and the federal and provincial governments to ensure the effort is successful.

Saving Wild Leeks from Climate Change

Historically, wild leeks were found in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, but as climate change warms up temperatures, their range is shifting northward. With Lake Superior and the province of Ontario to the north, this shift poses a problem for the Bay Mills Indian Community, for whom the plants are a vital cultural component.

Wild leeks grow in a relatively small area of land near the community, which is dominated by swamp conifers and shoreline, said Aubrey Maccoux-LeDuc, an environmental specialist with the Bay Mills Biological Services Department. Leeks prefer the cool, moist habitat found in upland hardwood forests.

Climate change is making conditions hotter and drier, and stressing out the plants, which are already slow to reproduce. Due to the Canadian border, the Bay Mills Indian Community, a US federally-recognized tribe, can’t simply follow the plants across the boundary. To combat this, the Bay Mills community is taking the first steps toward trying to protect and conserve these plants into the future.

The tribe has received a three-year, US$40,000 grant through the US Great Lakes Restoration Initiative for a population assessment of wild leeks in the area.

Maccoux-LeDuc said this should help gauge how many plants are there now and how quickly they regenerate, along with how many are mature plants, how many are younger and still growing and how many new plants sprout each year. This will help determine what, if any, restoration work will be necessary on the part of the tribe.

“If there is a need, we are hoping we can continue to provide sustainable patches of this plant for the Bay Mills members to harvest,” Maccoux-LeDuc said. “Because if they have to drive two to three hours one way just to harvest, people are not going to. And when that happens that’s an unfortunate loss to a piece of culture.”

Due to COVID-19, the field work won’t begin until 2021, Maccoux-LeDuc said, and will conclude in 2023 with a community workshop on the findings. This also will include lessons in sustainable harvesting techniques to ensure enough wild leek bulbs stay in the ground and continue growing in the area. Botanists with the US Forest Service and environmental staff from numerous Michigan tribes are partnering with Bay Mills in this work, she added

This isn’t the only resiliency project the Bay Mills Indian Community is working on. Maccoux-LeDuc said there’s an ongoing effort to see how infrastructure needs to be prepared for stronger storms and other extreme weather events. The tribe is involved in the binational Lakewide Action and Management Plans for lakes Superior and Huron.

This isn’t the only resiliency project the Bay Mills Indian Community is working on. Maccoux-LeDuc said there’s an ongoing effort to see how infrastructure needs to be prepared for stronger storms and other extreme weather events. The tribe is involved in the binational Lakewide Action and Management Plans for lakes Superior and Huron.

Kevin Bunch is a writer-communications specialist at the IJC’s US Section office in Washington, D.C.